From here, at least, nothing more could be heard. Through the trees the car was still visible on the top of the rise, and, to the left, the window with the closed shutters behind which the old woman was dying, motionless in her solitary bed, the sheet which was drawn up to her chin rising and falling with the regular rhythm of that continuous, calm and terrible rattle escaping from her lungs like the monstrous respiration of a giant, some playful mythological creature which had chosen its residence in the frail body of this woman in her death agony, so that these slow and interminable bellows could be heard like the trumpets of the Last Judgement,—dying, diligently dying, concentrated, focussed (solitary, arrogant and terrible) on the action of dying, in the dimness of the room where the summer’s powdery light penetrated only through the slit between the two closed shutters: a T whose crosspiece, shaped like a thin triangle lying base upward, corresponded to the interval between the top of the shutters and the window frame, and which slowly shifted from right to left, somewhat distended toward noon, then again diagonally lengthened again, all between morning and evening: like the initial of the word Time, an impalpable and stubborn letter trailing in the moribund odor, the stale and moribund fragrance hanging in the air: the smell of cheap eau de cologne the nurse bathed her in, and that ineffable, obsolete and ashen odor of faded bouquets which seems to float forever in the rooms of old ladies, around mirrors reflecting their worn faces, like the discreet, fragile, slightly rancid exhalation of faded days…

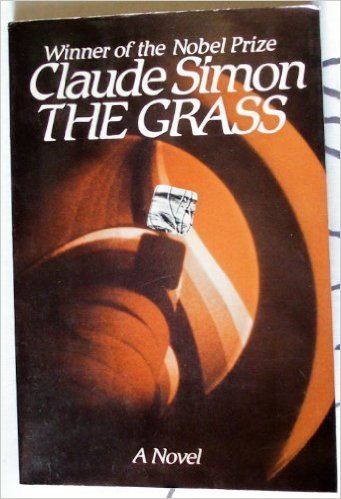

Source: The Grass by Claude Simon »

Tagged in: women

You may also like